The Quivering Cavern-Light of Good and Evil

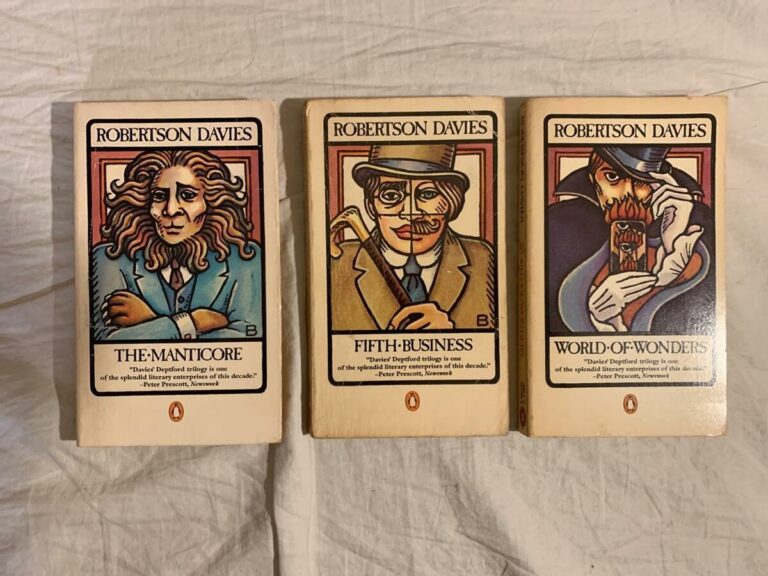

I’ve been influenced by many novels but certainly, the most profound – and the one that set me on a writer’s journey – was Fifth Business by Canadian author, Robertson Davies. It’s part of a trilogy – The Deptford Trilogy: The Manticore and World of Wonders completing the canon.

I was introduced to the novel in the seventh grade in Toronto and from then on, was obsessed with Davies’ ability to make a meal out of debating the roles that God and the Devil play in our lives.

“I am willing to accept the notion that although the Devil is a very clever fellow, he is no match for some ninny who is merely good… And what is this goodness? A squalid, know-nothing acceptance of things as they are …” (41).

In Fifth Business, Davies recounts a quotidian existence brimming with evil acts – some concrete, others intangible – all committed under the auspices of devotion. It is the year 1917 and Reverend Amasa Dempster is dispensing a brutal beating to his ten-year-old son, Paul Dempster. Paul’s transgressions are slight – the result of normal childhood mirth. But for a resolute Presbyterian minister in a small puritanical village, severe punishment is an imperative part of a parent’s repertoire. For in Amasa’s mind, punishment will save his son from real and imagined evil. It is the beginning of Paul’s acquaintance with the duplicity of human nature. As an adult, Paul recounts how his father would preface every beating he received with Proverbs 13:24: “He that spareth his rod hateth his son; but he that loveth him chasteneth him betimes” (947).

Paul Demptser will go on in book three – World of Wonders – to become Magnus Eisengrim – world renowned master magician. It’s a fitting and magnificent trajectory for a character with such humble origins. Dempster ends up assuming unfathomable power as Eisengrim and realizes divine retribution for the torment he’s endured – not just as a child, but later as a young man. What I most love about this series is Davies ability to traverse the very fine line between what is tangible and what might be influenced by forces we have no understanding of.

The following paragraph is spoken by the character of Liesl (Lieslotte Vitzliputzli), and it remains one of my favorite passages in a novel:

“…It was a sense of the unfathomable wonder of the invisible world that existed side by side with the hard recognition of the roughness and cruelty and day-to-day demands of the tangible world. It was a readiness to see demons where nowadays we see neuroses, and to see the hand of a guardian angel in what we are apt to shrug off ungratefully as a stroke of luck. It was religion, but a religion with a thousand gods, none of them all-powerful and most of them ambiguous in their attitude toward man. It was poetry and wonder which might reveal themselves in a dunghill, and it was an understanding of the dunghill that lurks in poetry and wonder. It was a sense of living in what Spengler called a quivering cavern-light which is always in danger of being swallowed up in the surrounding impenetrable darkness.”

– Robertson Davies

World of Wonders

DJ