René Magritte: Master Forger and Surrealist Rebel

I picture René Magritte as a smartly attired dissident – a saboteur – who assumes an air of petit bourgeois contentment while adroitly discrediting the entirety of bourgeois reality – similar to Tom in “The Talented Mr. Ripley.” In the most recent – and terrific – rendition, Ripley slowly unveils his intentions. Questionable deeds require another pivot and one more distortion of the truth, until a labyrinthine journey of obfuscation confounds everyone around him. This lack of immediate answers is what propels the plot – what one might call a ”Chefs Kiss” of deceit, where each deed is connected to the next in ways the viewer can’t even know.

René Magritte

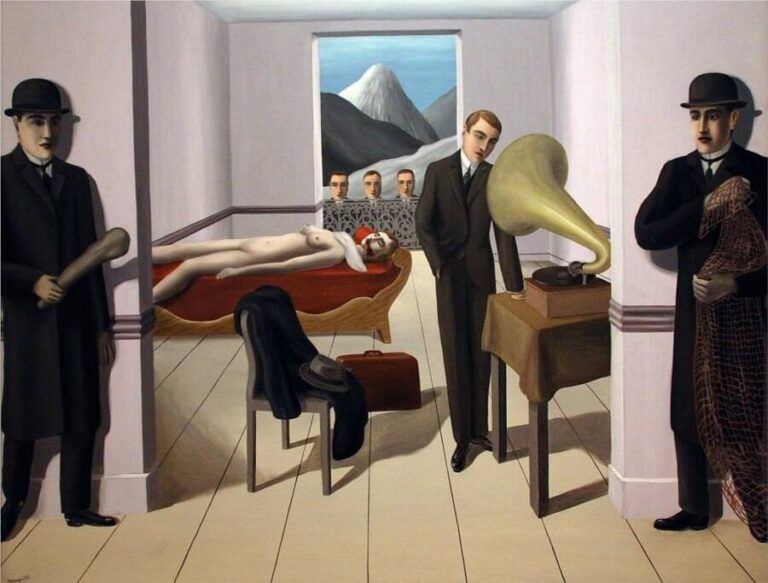

The Menaced Assassin

(Belgian, 1898-1967)

Magritte’s work traverses a similar, deceptive journey. He deceives the viewer by rendering mediocre objects but presents the images in such a way that our consciousness is jolted. Magritte forces us to question our passive, regimented, existence and consider what might happen if we stepped out of pre-conceived cultural boundaries. What lay just beneath the veneer? Do we dare confront it?

Magritte’s first exhibition in Brussels was greeted with vehement criticism. This prompted a move to Paris, which connected him with the surrealist circle and lead Dada, André Breton. Spiritual life, mysticism, and a search for meaning became enduring themes in Dada literature and art. The concept of “chance” figured prominently in the Dada school. Hans Richter, a Dada filmmaker stated in reference to the Dada manifesto: “For us, chance was the unconscious mind…Adoption of chance had another purpose, a secret one. This was to restore to the work of art its primeval magic power and to find a way back to the immediacy it had lost through contact with … classicism.” [1] It is here that we meet René Magritte and his world of twisted and implied meanings.

The Menaced Assassin presents a narrative puzzle that can’t be solved. The contents are patently real, but the tableau is deeply disturbing. Three men wear the same clothing – one has removed his overcoat and bowler hat. A briefcase sits on the floor. The suits and briefcase – accoutrements of the bourgeois – are wielded as symbols. Magritte’s resolute masses linger in his canvas and bear witness to the vile desires lurking just beneath their conscious selves. Center stage is what appears to be sadistic crime and we, cast as voyeurs, cannot look away. Magritte has revealed our ghoulish natures. Three identical spectators peer into the room. There has been no effort to distinguish the players. They are interchangeable – replicas of each other – symbols of mediocrity. The naked – and we presume dead – body of the women lay on a red velvet chaise lounge. Blood streams from her face and a towel is draped on her chest. Snow-capped mountain ranges can be viewed from the window – along with the peeping toms. The man in the room, seemingly indifferent to the dead woman, turns his attention to the gramophone. Did he just kill her? Is he pondering what music should accompany his deed? It really doesn’t matter. The scene is almost comical as the two men that flank the frame wield a club and net, respectively. Their indifference to the woman’s fate is evident in their expressions.

The rigidness of Magritte’s characters reflects the conformity that accompanied the rise of a mechanical age. Commodification was the end product of efficiency in production and to maintain status quo, every worker sought to acquire things. From this conformity, Magritte responded with contradictory images that revealed a “sensation of mystery”.[2]

The incongruity of Magritte’s canvas presents us with a vexing situation but it also infers the duplicity of human nature. The rational mind cannot use reason to resolve the conflict and yet we attempt to construct a sensible scenario.

The idea of artifice typifies Magritte’s work but it’s not the artifice of a concept. it is the unrelenting and encompassing ambition devoted to the acquisition of “things.”

Magritte pronounced this ambition as mundane and conformist. He sought to deconstruct the bureaucratization that had become the new economic paradigm. During the Nazi occupation of Belgium, Magritte supported himself through the production of fake paintings of artists such as Manet, Picasso, and Van Gogh. His brother, Paul and fellow Surrealist Marcel Marien, were in on the deception and orchestrated the sales of the fakes to collectors. Then, Magritte’s repertoire expanded to the production of forged 100-franc banknotes – perhaps not as lucrative as a fake Picasso, but still, when times are tough, the tough pivot. That he was not adverse to becoming a grifter, is testament to the decidedly un-bourgeois grit and resolve he was able to muster in times of scarcity.

Magritte reached into the recesses of the unconscious and created disparate and extraordinary work that horrified audiences – then. After nearly 70 years, advertisers still look to him for inspiration. It would appear that we have, indeed, embraced our dark sides.

[1] Jacques Meuris. Magritte, (Taschen, Los Angeles, 1991) 13, Magritte’s closest friend, Scutenaire, states in one of his numerous writings about his friend that, as a young child, Magritte first experiences what he called the “sensation of mystery” in Gilly, France when a balloon crashed on the roof of a shop and stern-faced men in leather clothes and helmets had to drag down “this long soft thing”.

[2] Fred S. Kleiner and Christin J. Mamiya. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages, 11th Edition, (Harcourt College Publishers, 2001),1023.

— Deborah Johnstone